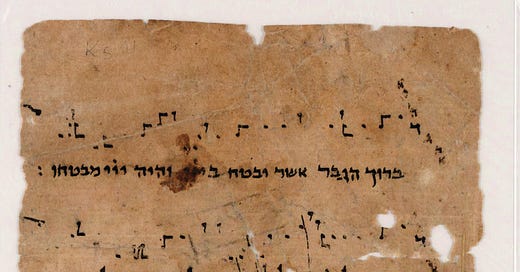

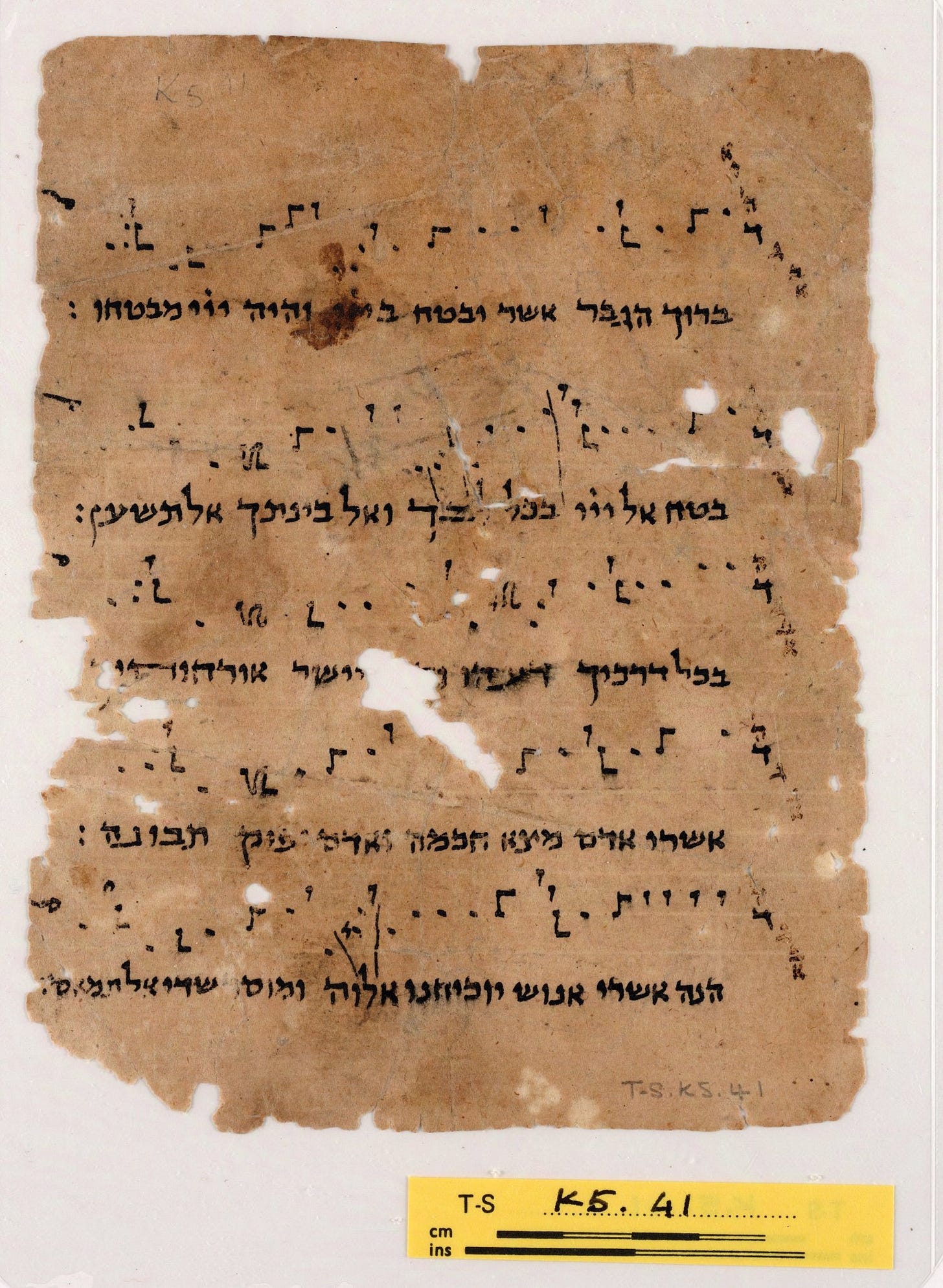

This, right here, is the earliest known musical notation of a Jewish song (and it’s a song that’s notated with trope, cantillation marks for liturgical recitation).

The story of how we got this, the mystery it caused, and the fascinating backstory of the likely author of it are all a pretty good story. So I thought I’d tell it! Thanks to the archivist…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Life is a Sacred Text to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.